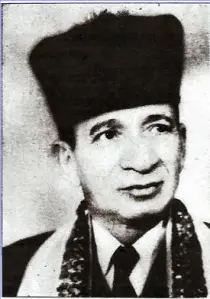

hazzan Adolph Katchko

Dear Friends,

With the support of Hazzan Katchko's grand-daughter, Hazzan Debbie Katchko-Grey, we are currently recording and publishing some important and previously unpublished material. These also include five Friday Kiddush pieces never published.

Hazzan David Presler

Israel

A history of Hazzan Adolph Katchko

Here is the Playlist

In 1949 Adolph Katchko, who served as hazzan at Congregation Anshe Chesed in New York City in the years leading up to and immediately following World War II, put forth the following definition of “Modern hazzanut”:[It] combines the long singing phrase with the use of a reciting note, on which as many words are fitted as the prayer context will allow. This combination is initiated on consecutive ascending degrees, all of which are typical of the particular mode, until a high tessitura is reached. At that point, the process traverses itself downwards.

The progeny of this marriage between fast-paced declamation and florid cadential flourishes was as legitimate in the 20th-century synagogue as it was in the 20th-century church. The 1904 Solèsmes Edition of the Graduale (compendium of chants for the Mass) restored a free speech-rhythm that made it possible to wrap melismas in an envelope of rapid delivery.

Like most great cantors, Adolph Katchko, born in Varta, Kaliscz, Russia, was a child prodigy. He began singing publicly at age six, with the choir of Jonah Shochet. As a young man he studied voice and composition in Berlin, and emigrated to the United States in 1921.

He served various congregations for six years before being appointed cantor at Temple Anshe Chesed in Manhattan, where he remained for 24 years until his retirement. He taught many colleagues privately, and published numerous compositions of his own, including Avodath Aharon, a Friday Night service for cantor and mixed choir.

Normally, a voice as fully resonant as his would not lend itself to long coloratura. Yet its extraordinary flexibility enabled him to execute such passages flawlessly and tastefully. Katchko’s virtuosity made him comfortable in either the Orthodox or Reform style of service, and his hazzanut was highly regarded in all three main branches of American Judaism.

His own congregation was among the 10% of Conservative synagogues that employed an organ during regular worship services, and not just for weddings. Katchko was beloved by his cantorial students at the Reform Hebrew Union College’s School of Sacred Music, which published his two-volume Thesaurus of Cantorial Liturgy–Otsar Ha-hazzanut. It is no accident that Katchko’s Otsar ha-hazzanut met with the grateful approval of students at both the Reform and Conservative cantorial schools for more than a half-century.

Adolph Katchko’s music–as well as his unforgettable voice and performance style–are now accessible to tall who appreciate the cantorial art.

His granddaughter, Deborah Katchko-Gray, who serves as cantor at Temple Shearith Israel in Ridgefield, Connecticut, compiled a book and companion CD entitled Katchko: Three Generations of Cantorial Art. Released by Tara Publications (Jewishmusic.com) in 2009, it contains transcriptions of previously unknown compositions by her grandfather, and recorded interpretations of them by her father, Cantor Theodore Katchko, a bass-baritone like his father before him. The book includes Deborah’s personal reflections on her father’s and grandfather’s hazzanut, plus family photos–such as a priceless undated shot of Adolph being mock-coached by Zavel Kwartin atop an unnamed mountain in upstate New York. There are also several noteworthy articles and talks published by her grandfather.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel once said of the hazzan: “He stands before the Ark not as an individual, but as a congregation.” This was particularly true on Yamim nora’im, when the scenario might be described as an anonymity of individuals, with Everyman represented by the Whole House of Israel.

Logistically, the stage was set by its built-in devotional motivation, its large number of congregants, and its elaborate liturgical imagery. But the High Holiday dynamic that prevailed in leading American Conservative synagogues like Anshe Chesed in New York at mid-20th century was ultimately turned on by the same switch that activated the most humble Daily Minyan all year long-the magic of hazzanic chant sung by master improvisers like Adolph Katchko–to which worshipers instinctively responded.